Ovarian Cysts, Follicular Cysts, and Luteal Cysts

Ovarian cysts are pathological ovarian follicles that have not undergone ovulation, typically measuring between 25 mm and 50–60 mm in diameter. It is important to note that postpartum “cysts” occurring within 40 days after calving are considered physiological and not pathological. Only after this period, if the cysts persist, can they be identified as a problem requiring intervention. The exact causes of ovarian cysts remain unclear. They are most likely the result of environmental and genetic factors, as well as nutritional deficiencies (including energy, vitamins, micro- and macroelements), previous uterine inflammations, and other reproductive system diseases. These factors disrupt the hypothalamus-pituitary-ovary axis, leading to abnormal secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH), which is essential for triggering ovulation. An insufficient LH surge prevents the ovarian follicle from rupturing, ultimately leading to anovulation. As a result, cows may experience irregular estrus, lack of estrus, or symptoms of nymphomania, which may resemble the early stages of estrus.

The most common treatment for ovarian cysts involves pharmacological agents aimed at stimulating follicular rupture. The most frequently used drugs include GnRH analogs (gonadotropin-releasing hormone), which stimulate the release of LH and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), or progestogens. These treatments seek to induce ovulation in deactivated follicles. If the response to pharmacological treatment is insufficient, more invasive methods may be employed, such as ultrasound-guided aspiration of cystic fluid. This technique allows for the safe removal of fluid from the cyst, potentially restoring a normal ovarian cycle. However, this method is not widely used and requires careful monitoring and appropriate technical conditions.

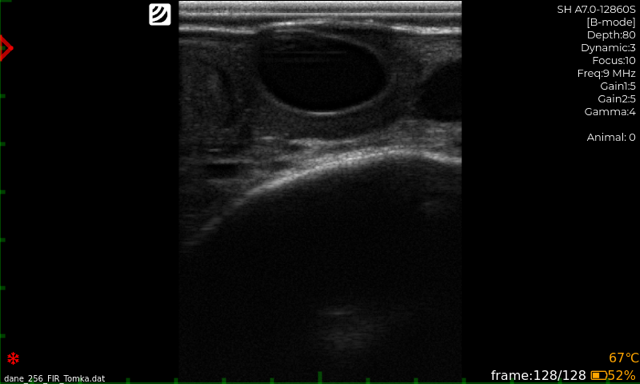

A less common type of ovarian cyst is the luteal cyst, which is a variant of follicular cysts that have undergone luteinization. This means that despite the absence of ovulation, the follicle transforms into a structure resembling the corpus luteum. Luteal cysts may produce progesterone, leading to irregular estrous cycles or their complete absence. The most effective treatment for luteal cysts is the administration of PGF2α analogs, such as cloprostenol, which have a luteolytic effect, inducing regression of the corpus luteum. It is important to note that the cyst wall must be thick enough to respond to prostaglandin treatment. A wall thickness greater than 3 mm is typically used as a criterion for classifying a cyst as luteal. If there is insufficient response to PGF2α, treatment similar to that for follicular cysts—such as the use of GnRH analogs—may be considered. Aspiration of luteal cysts is not recommended, as this method is generally ineffective and unfavorable for further treatment.

Figure 1 Lutein cyst (diagnostic image taken using iScan 3)

Diagnosis and Classification of Ovarian Cysts

One of the key challenges in treating ovarian cysts is their accurate diagnosis and classification. Proper identification allows for appropriate treatment selection, increasing its effectiveness. Misclassification of cysts can lead to ineffective therapy and unsuccessful treatment outcomes. The most precise diagnostic tool for detecting ovarian cysts is ultrasonography. Ultrasound examination allows for an accurate determination of cyst size, structure, and fluid content. Additionally, in the case of luteal cysts, ultrasound helps assess cyst wall thickness, which is crucial for treatment planning. Doppler ultrasound is also highly effective, as it enables the observation of blood flow within the cyst wall, providing valuable insight into whether the cyst will respond to prostaglandin therapy.

Mycotoxins as a Risk Factor for Ovarian Cysts

Mycotoxins—toxins produced by certain mold fungi—can significantly impact reproductive health in cows and contribute to the occurrence of ovarian cysts. Mycotoxins can disrupt normal hormonal function, including the secretion of gonadotropic hormones, leading to ovulation and estrous cycle disorders. The ingestion of mycotoxin-contaminated feed, particularly those containing aflatoxins, zearalenone, or ochratoxins, can interfere with estrogen and progesterone production, impairing the normal development of ovarian follicles and increasing the likelihood of cyst formation.

To minimize the risk associated with mycotoxins, several measures can be implemented, such as mycotoxin adsorbents (e.g., bentonite or zeolites), which bind toxins in the digestive tract, preventing their absorption. Additionally, incorporating toxin-counteracting additives into feed, such as vitamins (e.g., vitamin E and C), which support immune function, as well as yeast-based supplements, can improve gut microbiota health and aid in detoxification. Regular feed testing for mycotoxins is also essential to reduce the risk of toxin ingestion and prevent related reproductive issues.

DVM, Michał Barczykowski